NEW YORK — Entrepreneurs are utilizing new technologies to bridge the gap between where food is grown and where it is consumed.

San Diego-based BlueNalu, Inc. is pioneering cellular aquaculture, a process by which living cells are taken from fish and grown using culture media to create seafood.

“(Seafood) is one of the most vulnerable supply chains on the planet,” said Lou Cooperhouse, co-founder and chief executive officer at BlueNalu, during a virtual Town Hall hosted by accounting and consulting group Mazars. “Global demand for seafood is at an all-time high. The problem is that our supply is increasingly diminishing.”

A variety of overlapping factors, including illegal fishing and overfishing, warming oceans, plastic pollution, habitat damage, toxins, contaminants and inconsistent quality of freshness have contributed to the diminishing supply, Mr. Cooperhouse said. Other issues like mislabeling, occupational hazards and price volatility add to an already stressed system.

“Prices are going higher over time and are anticipated to grow increasingly higher in the years to come,” Mr. Cooperhouse said, adding that BlueNalu has been working to bring down the cost of its formulation to reach price parity with conventional seafood products.

As it scales, the company could potentially offer a price discount, he said.

BlueNalu recently expanded its production and R&D capabilities with a new, 38,000-square-foot manufacturing facility in San Diego that includes a pilot-scale production plant. Eventually, it aims to build similar plants around the world, each with the capacity to produce enough cell-based seafood to feed millions of residents.

“Today we might be importing seafood 7,000 miles, 9,000 miles from Southeast Asia to New Jersey, and that's a 30% bycatch with a 60% yield at the foodservice operator level,” Mr. Cooperhouse said. “In our case we're making a product with no head, no tail, no bones and no skin. It’s just the filet.”

The pilot plant will help BlueNalu bring its first products to test markets within the next 12 to 18 months. The company currently is focused on several species that typically are imported, overfished or difficult to farm-raise, including mahi mahi, tuna, red snapper and yellowtail amberjack.

The idea is to compliment or supplement rather than disrupt the current supply, Mr. Cooperhouse said.

“Why would we disrupt an industry that’s doing well or focus on a species that currently isn’t an issue?” he said.

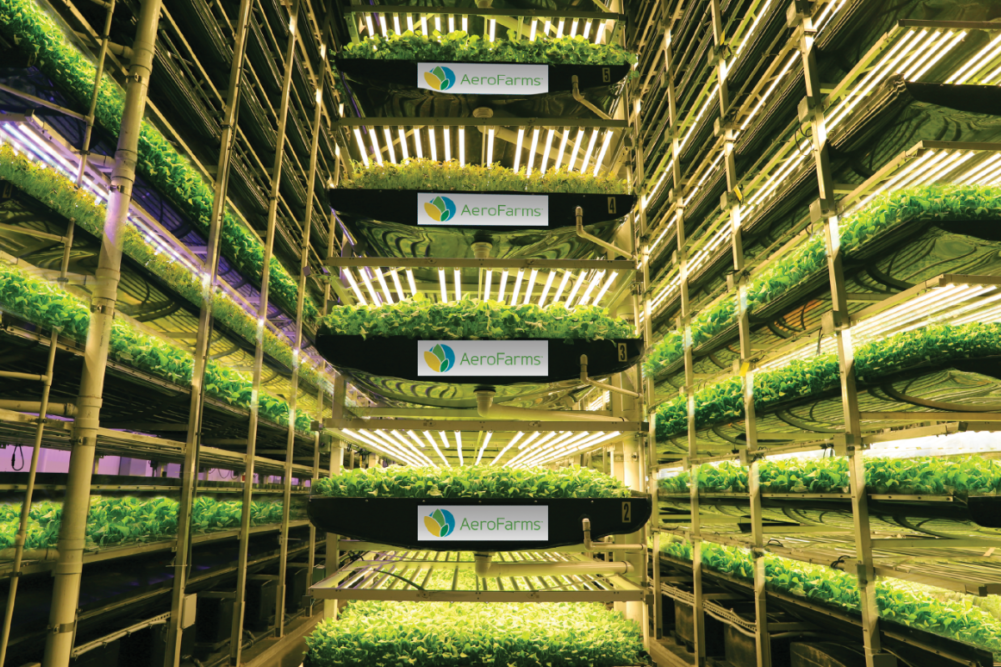

A similar mindset is behind Aero Farms, a Newark, NJ-based sustainable indoor agriculture company.

“Seafood is traveling thousands of miles, and it’s the same for produce,” said Marc Oshima, co-founder and chief marketing officer at AeroFarms. “How can we bring farms closer to where people are and bypass what is a very complex supply chain?”

The company repurposes unused industrial spaces into indoor farms that use 95% less water than conventional agriculture and a fraction of the land space.

“We're misting the roots with the right amount of water and nutrients in a very targeted way,” Mr. Oshima said. “It leads to a faster growing process and is much more efficient.”

AeroFarms’ main focus is baby greens, which are supplied to foodservice operators and sold to retailers under the Dream Greens brand.

Because they are grown independent of season and weather, the products offer more consistent quality, price and year-round availability, Mr. Oshima said.

The company also is collecting data to optimize crops for taste and nutrition.

“We’re thinking about what the consumer is looking for and delivering on a lot of those benefits,” Mr. Oshima said.

Along with keeping transportation to a minimum, increasing yield and offering more nutritious produce, indoor farming may compliment traditional agriculture by accelerating seed development.

“Typical seed breeding is about a seven-year process,” Mr. Oshima said. “With our growing process, we can have up to 30 harvests in a year. Each one is a learning opportunity.”